By Amara Thornton, CBRL Centennial Award holder and Honorary Research Associate, UCL Institute of Archaeology

The 100th anniversary of the foundation of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem is the perfect opportunity to look into the history and significance of this institution. As a CBRL Centenary Award holder, I’ve been investigating one of the School’s early students – George Horsfield. My research during the course of the project has centred on his work at the first intensive scientific excavations at Petra in Transjordan (as modern Jordan was called at that time) in 1929.

Born in Leeds in 1882, George Horsfield originally trained as an architect and worked in the Gothic Revival style. After service in the First World War (including taking part in military campaigns in Gallipoli and on the Somme) George applied to become a student at the British School in 1923. The School had been open for only a few years, but through its excavations at Tell Harbaj and Tanturah George gained experience managing an excavation, as well as using his architectural draughtsmanship to produce elegant plans of the sites.

John Garstang was the BSAJ’s first director, and he became Horsfield’s archaeological mentor. It was through Garstang’s facilitation that Horsfield was sent in 1924 from Palestine to Transjordan, in order to turn his archaeological and architectural expertise to the restoration of Jerash, where plentiful extant remains marked the site of an important city during the Roman period. In clearing the site and beginning the restoration process, he also made discoveries, including a Roman statue head now in the Amman Museum (seen on the far right of this photograph). This head was claimed at the time of discovery to be a portrait of Jesus Christ.

The Institute of Archaeology at UCL now holds an archive relating to George Horsfield’s work in Transjordan, where in 1926 he became Chief Inspector of the newly established Department of Antiquities. Three years later, George Horsfield began excavations at Petra with financial support from Henry Mond, Lord Melchett. With fellow Brit Agnes Conway, a historian, archaeologist and curator, he co-wrote a “Petra Excavation Fund Diary”. Through the support of the CBRL, I have now turned this diary into a digital resource, www.petra1929.co.uk. In addition to the diary there are contextual essays on Transjordan during the British Mandate, Archaeology and Tourism in Mandate Transjordan and representations of Petra in wider culture and an essay about the genesis of the excavation. It also includes a list of people and places mentioned in the diary.

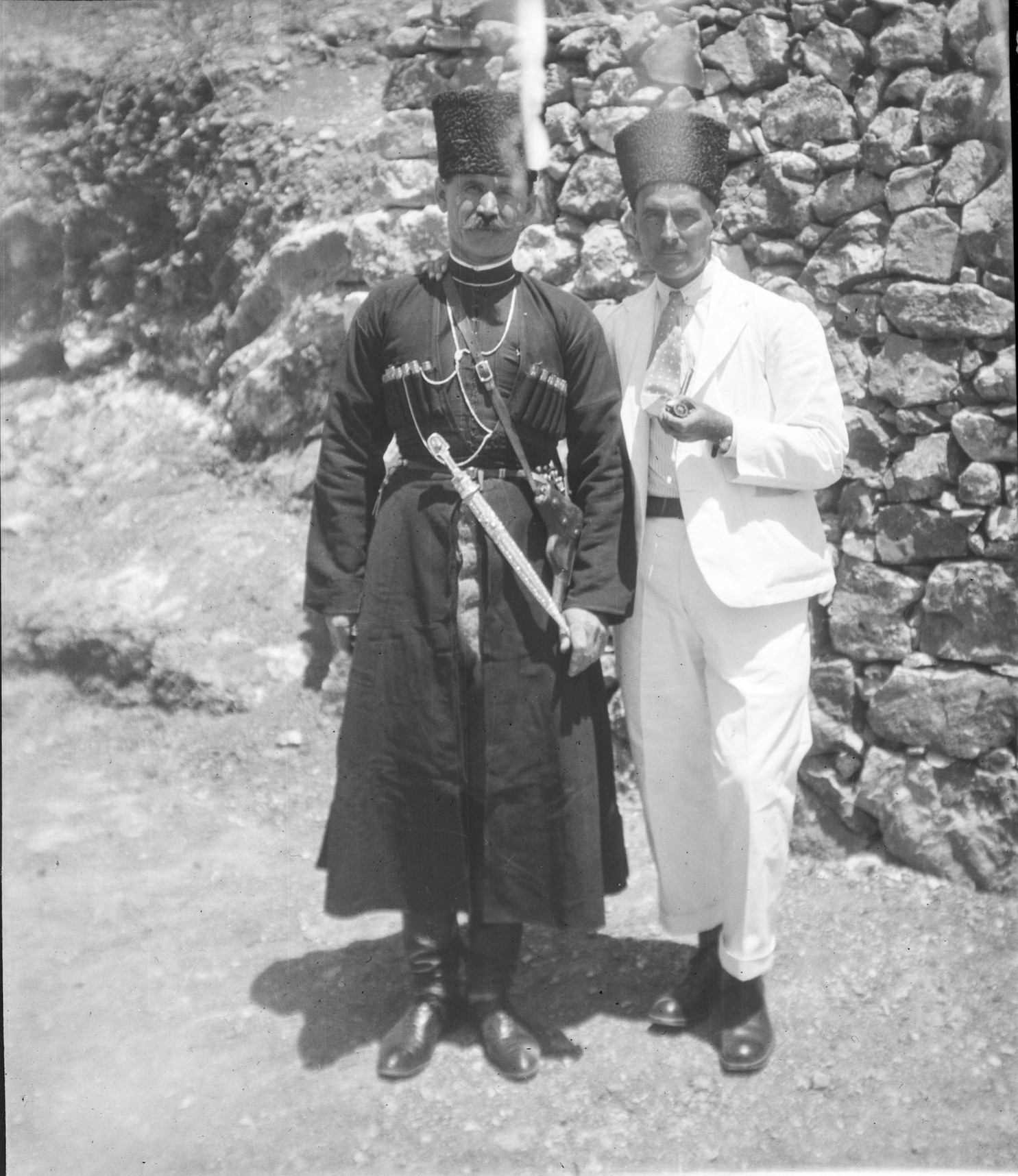

The diary charts the excavation day by day, running from 21 March 1929 to 14 May 1929. Each dated entry has been keyworded so that mini-narratives can be pulled out of the diary. For the most part, George and Agnes each contributed a section to each day’s entry, so that both their work is represented. The work of the other two researchers – Ditlef Nielsen and Tawfiq Canaan – is also described, but barring a few exceptions their voices are not represented in the diary text. Keywording the diary entries helps to highlight the role of the workforce on the excavation. So, for example, the contributions of George Horsfield’s most trusted workers becomes more visible. These were a small group of Circassian men; they had been working closely with Horsfield at Jerash.

Newly digitised images accompany diary entries and the essays and lists. These are mainly from photographic negatives taken by Agnes Conway during the course of her travels and work in Transjordan. George Horsfield and Agnes Conway were married in 1932, a few years after they excavated Petra; it was the site, indeed, that drew them together in the first place! Agnes’s photographs are fascinating representations of archaeological life, and spending time digitising some of the negatives helped to illuminate the work and the diary she and George produced.

I combed through the indexes to the negative books looking for images that I could add to illustrate the people and places George Horsfield and Agnes Conway encountered during the course of their Petra work. One of my favourite discoveries in the digitisation process was a photograph of George Horsfield and Mahmud Charish, one of the Circassians mentioned frequently in the diary, among the Horsfield negatives.

Further reading:

Thornton, A. 2014. The Nobody: Exploring Archaeological Identity with George Horsfield (1882-1956). Archaeology International 17, 137-156. DOI: 10.5334/ai.1720.

Dr Amara Thornton is an Honorary Research Associate at the UCL Institute of Archaeology. She is founder and Coordinator of the Institute’s History of Archaeology Network, and also Principal Investigator on Filming Antiquity, a digitisation and research project for historic excavation film footage. In June 2018 her first book Archaeologists in Print: Publishing for the People was published by UCL Press.

The views expressed by our authors on the CBRL blog are not necessarily endorsed by CBRL, but are commended as contributing to public debate.